Wednesday, July 30, 2008

Father who rebuked CPS loses right to see son

Follow up from yesterdays article --

Follow up from yesterdays article --Another child's death on CPS' watch raises new questions

Today's Story came from Legally Kidnapped's blog over there >>

Thanks LK!

Father who rebuked CPS loses right to see son www.azstarnet.com ®

Visitation canceled after dad and boy talked about story on kid's late brother

By Josh Brodesky

arizona daily star

Tucson, Arizona Published: 07.30.2008

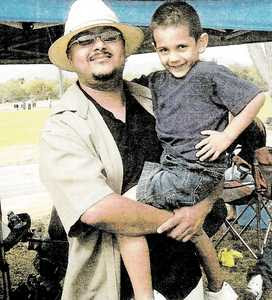

A father whose son was killed while under CPS watch had his visitation with his surviving older son cut off after talking to the boy about a Sunday Arizona Daily Star story on his brother.

Oscar Silva Jr. was notified his regular Tuesday visit with 8-year-old Oscar III was canceled just a few hours before the scheduled get-together. He was told there will be no further visits until at least next week, when there will be a meeting with his Child Protective Services case manager.

He normally has visitation Tuesday and Thursday afternoons and every other weekend.

Agency spokeswoman Liz Barker Alvarez confirmed Silva's visitation rights have been suspended, but she couldn't say specifically why.

"There were certain behaviors on Mr. Silva's part that went against the case plan and the visitation agreements, and those behaviors were seen as potentially harmful to the child," Barker Alvarez said.

Silva said Oscar III saw the Sunday story, which included a picture of his brother, and he asked to read it.

"I went ahead and let him read it. I wanted him to know what was going on," Silva said.

Silva's younger son, Fabian, 4, died in January from blunt-force trauma to the head. His mother's boyfriend, Alejandro Miguel Romero, 25, has been charged with child abuse and manslaughter.

CPS opened a file on Fabian Silva in October after two doctors examining him for a throat infection reported signs of suspected abuse. Oscar Silva and other family members have criticized the CPS investigation, saying they were never interviewed despite repeated requests to be heard.

Silva said his case manager told him Tuesday that he had violated a verbal agreement with CPS not to talk about the case with Oscar III, and therefore his visitation rights were being suspended. Oscar III now lives with great-grandparents on the mother's side, Silva said.

Barker Alvarez would not say if the unacceptable behaviors involved reading the news story and/or talking about it.

"We do have a child here, who has to deal with a lot. I am giving you as much information as I can," she said. "The decision was made in the child's best interest."

Silva said he felt the move was in retaliation for both the Sunday news story and a $5 million claim he filed against CPS last week.

He acknowledged that under the verbal agreement, he is supposed to contact CPS if his son asks about the case and his brother's death.

"On this Sunday, I didn't ask," he said. "I didn't call no one. I just let him read the article. It was a verbal agreement."

Attorney Jorge Franco Jr., who is representing Silva, called the suspension "off the charts."

"It happens literally two days after the article appears," he said. "That can't be a co- incidence. It has to be tied to the article."

"It's the ultimate in retaliation," he said. "If they are suspending his visitation because the child read the article and then had a conversation with the father about the article, and nothing more, that's outrageous and appalling."

Contact reporter Josh Brodesky at 807-7789 or jbrodesky@azstarnet.com.

Original Article- Father who rebuked CPS loses right to see son www.azstarnet.com ®

My two cents..

From working with many families who have had their children "removed" or lost visitation.. I can say .. THIS IS TYPICAL of CPS ..

The public needs to be outraged and they need to begin to see the abuses of our system and how it's effecting the future of America... OUR CHILDREN!

People ... OPEN YOUR EYES.. The Child Protection busniess and some/all/most of our Family courts are NOT DOING WHAT IS IN THE BEST INTEREST OF THE CHILDREN.. in fact THEY ARE COLECTIVELY DESTROYING OUR CHILDREN'S LIVES! While getting outrageous federal funding incentives via YOUR TAX DOLLARS.. to do it!

Deadbeat dad wanted to kill judge, says prosecutor

Tuesday, July 29th 2008, 7:24 PM

A jailed deadbeat dad bragged to other prisoners that he would kill the judge "who gave his house away" to his ex-wife, the Suffolk district attorney said Tuesday.

Brian Orkiszewski, 49, told an inmate at the county's minimum security jail in Yaphank that the Family Court judge "will have a big surprise when I knock on his door," DA Thomas Spota said.

Orkiszewski was upset the judge awarded the $300,000 made from the sale of his East Northport home to his former spouse, Lynda, prosecutors said.

"He made no bones about it. He was shopping for a handgun to murder the judge," Spota said. "There is no doubt in my mind that this man was serious about what he intended to do."

Defense attorney Anthony Grandinette called Orkiszewski's comments jailhouse ranting by a frustrated man down on his luck.

"He's frustrated. He's angry. He's depressed. He said some stupid statements off the cuff," Grandinette said of his client, a former Verizon employee. "However, there was no intent of carrying out those words that he spoke in frustration."

Spota said detectives intercepted a note Orkiszewski sent to another inmate asking for help in purchasing a handgun.

"He wrote that after his release from Yaphank, he needed to shop right away at 'the hardware store,' which are the code words he used for gun supplier," Spota said. In another letter, Orkiszewski "asked for the telephone number of the person from whom he could obtain 'a good plunger,' a code word for a gun," Spota added.

Authorities would not release the name of the Family Court judge Orkiszewski allegedly wanted to kill, but Spota said it was not the judge who sent Orkiszewski to jail three months ago for failing to pay child support.

Suffolk Judge William Kent presided over the Orkiszewskis' divorce, though authorities would not confirm he was the target of Brian Orkiszewski's rage.

Orkiszewski was divorced three years ago. More than a year ago, he fell down a fire escape while working for Verizon, fracturing three vertebrae and rupturing two spinal disks, Grandinette said. The injuries left him unable to work and pay child support, the lawyer said.

Appearing haggard and notably uncomfortable, Orkiszewski ambled into Suffolk County Judge Robert Doyle's courtroom yesterday to plead not guilty to grand jury charges of conspiracy and criminal solicitation. Doyle ordered him held in jail on $250,000 cash bail.

bharmon@nydailynews.com

Original Article- Deadbeat dad wanted to kill judge, says prosecutor

My three cents..

FIRST THO...

Before anyone wants to start rumors..

I WILL SAY .. I DO NOT CONDONE what this man did.. said.. or didn't do or didn't say..

HOWEVER..

I will say .. until you have walked in his shoes.. until you have been abused by a Family Court Judge.. don't make judgement calls..

I will say .. I have been abused by our justice system beyond what the average person would be able to tolerate.. and although I've never said I wanted to kill anyone.. I have wished horrible bus accidents or Bear/Shark attacks.. or being struck by lightening for those that knowingly abuse Innocent parents and children.

But .. again the difference is.. I pray when these horrible acts of God happen to those that caused the emotional trauma of me and my family (others and their families) .. I pray they LIVE very long miserable lives after the fact... I pray they live .. crippled.. in pain.. and vulnerable to others.. perhaps then they will then understand what they viciously put innocent parents through.

DOJ wins fraud case against National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges

DOJ wins fraud case against National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges

Thurston County Family Court Reporter

In part it says..

In April, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (“NCJFCJ”) agreed to pay $300,000 to the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) in full settlement of allegations that had been raised about how NCJFCJ recorded staff time on federally funded projects, and allegations about possible conflicts of interest.

For more click the links above...

Monday, July 28, 2008

N.J. Legislator Resigns Amid Child Porn Probe

NEW YORK -- Veteran Democratic New Jersey Assemblyman Neil Cohen has resigned amid an investigation into alleged possession of child pornography on his legislative office computer.

NEW YORK -- Veteran Democratic New Jersey Assemblyman Neil Cohen has resigned amid an investigation into alleged possession of child pornography on his legislative office computer. In a brief resignation letter to the Clerk of the General Assembly Monday, Cohen said his resignation is effective immediately.

News 4 New York reported Friday that the seven-term assemblyman has been hospitalized under psychiatric observation Thursday night, after investigators seized computers from his office on Stuyvesant Avenue in Union.

It was two fellow democrats who essentially turned in Cohen.

Sources told WNBC.com’s Brian Thompson that no decision was made as of Thursday night as to whether the 57-year-old legislator will face state or federal prosecution.

The investigation began after state Attorney General Anne Milgram received a tip, sources said. Her office seized the assemblyman’s Union Township computers Wednesday as part of the investigation, sources said. At least one of the computers was assigned to him as part of his work in the legislature.

The two confirmed Thursday to News 4 New York: “As the facts became apparent in our office, we notified the appropriate agency and will continue to assist in any way possible,” they said in a joint statement. “While it was our proactive steps that led the investigation to this point, we are appalled at what has transpired.”

They added that both have known Cohen for more than two decades.

“We know him as a compassionate caring individual, but if the allegations prove true, clearly there was a side to him neither of us knew,” they said in the statement.

Cohen served in the Assembly from 1990 to 1991 and from 1994 to present. He is currently a deputy speaker.

In 2001, Cohen sponsored a bill creating a computer hotline to report child pornography and other Internet crimes.

Cohen also has been a leading backer of state stem cell research efforts.

The outspoken liberal Roselle resident shares an office with State Senator Raymond Lesniak and Assemblyman Joseph Cryan.

Original Article -

N.J. Legislator Resigns Amid Child Porn Probe - Politics News Story - WNBC New York

Rape suspect caught on security camera attacking teen boy on street

BY KAMELIA ANGELOVA and ALISON GENDAR

BY KAMELIA ANGELOVA and ALISON GENDARDAILY NEWS WRITERS

Sunday, July 27th 2008, 1:04 PM

Reham Ali in police custody after a surveillance camera apparently caught him attacking a teenage boy.

Brooklyn narcotics cops investigating suspicious activity seen on a security camera made a disturbing discovery Saturday: a senior citizen sexually assaulting a mentally retarded teenage boy.

Reham Ali, 65, was arrested for a sex crime after two city narcotics cops caught him holding down and sodomizing the 16-year-old between two parked cars in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, just before 7 a.m. Saturday.

A 24-hour security camera near Seventh Ave. and 64th St. showed Ali seemingly hiding something there, and two detectives went to investigate.

"The suspect had no idea that the camera was there, but it was a quiet block that time of the morning and he made no real effort to hide what he was doing," a police source said.

"He grabbed the kid and right there on the street, between the parked cars, attacked the kid."

The teen told police he had been on his way to meet a friend for a game of basketball at a nearby park when Ali walked up and propositioned him.

The teen, who attends a special education school, was scared and flustered. He walked faster, trying to get away from the creepy old man, sources said.

Ali, a married man with four grown children, followed the teen for at least two blocks, whispering what he wanted to do to the boy, another source said.

Ali then bear-hugged the boy and pulled him between two parked cars on a deserted stretch of Seventh Ave.

"The poor kid didn't know what to do," another police source said. He was taken to a nearby hospital for treatment.

Ali was charged with a first-degree criminal sex act, unlawful imprisonment and endangering the welfare of a child.

After he was busted, the retired construction worker confided to cops that "I did this before. I did it at home," in Pakistan, sources said.

Ali's wife was stunned by his arrest. Ali had told his family he was having an asthma attack and that he needed some fresh air, said one of his two daughters, Faria Ali, 26.

"This morning he said, 'I'm suffocating here. I'm going for a walk.' He's a good dad. He never did anything like this. He never bothered anybody," she said.

Original Article -

Rape suspect caught on security camera attacking teen boy on street

agendar@nydailynews.com

My two cents...

This degenerate was caught on camera.. forget jail.. forget sentencing .. forget trial.. CASTRATE THE BASTARD!

Children are dying from ADHD Drugs

Info for Parents who are pressured to diagnose and drug their children for ADD or ADHD. Story behind our Sons death caused from ADHD drug, Ritalin.

Info for Parents who are pressured to diagnose and drug their children for ADD or ADHD. Story behind our Sons death caused from ADHD drug, Ritalin.Between 1990 and 2000 there were 186 deaths from methylphenidate reported to the FDA MedWatch program, a voluntary reporting scheme, the numbers of which represent no more than 10 to 20% of the actual incidence.

This looks like an older article but worth sharing..

Death from Ritalin the Truth Behind ADHD

Another child's death on CPS' watch raises new questions

Long before 4-year-old Fabian Silva died, his older brother sent a letter to Child Protective Services saying he was scared of Alejandro Romero, his mother's boyfriend, who is now charged with killing Fabian.

Long before 4-year-old Fabian Silva died, his older brother sent a letter to Child Protective Services saying he was scared of Alejandro Romero, his mother's boyfriend, who is now charged with killing Fabian.But a CPS caseworker told police she thought Oscar Silva had been coerced to write the letter by his non-custodial father, and left the boys in the home even though two doctors had also reported signs of abuse and the boys' mother told her Romero smoked marijuana daily.

Alejandro Miguel Romero, 25, who had been found guilty of drug-paraphernalia possession and had been arrested on a previous domestic-violence complaint and a disorderly conduct complaint, was indicted last month on charges of child abuse and manslaughter in connection with Fabian's death Jan. 27 from a blunt-force trauma to the head.

Documents obtained by the Arizona Daily Star don't say whether CPS did a criminal background check on Romero after opening its investigation in October, in response to doctors' concerns about severe bruises to Fabian's groin and penis and elsewhere on his body that appeared to be from abuse.

CPS has refused to release Silva's case file, saying a new state law making such files public record will not take effect until September. Agency spokeswoman Liz Barker Alvarez would not comment, citing the pending litigation.

But a combination of police, medical and autopsy reports raise questions about the agency's handling of another case in which a child under its watch died.

Although Fabian's father and one set of grandparents contacted CPS in the fall, months before Fabian died, there is no evidence investigator Kathryn Kolton formally interviewed them.

It's also unclear if Kolton interviewed an aunt who was living in the home at the time, even though CPS investigators are required to interview all adults in the home. The aunt would later tell police she had concerns about Romero's drug use and how he treated Fabian.

Early warnings

In the days before Halloween 2007 Fabian had been throwing up and battling a headache that kept getting worse. Worried about his health, Fabian's mother, Marina Baker, took the boy to Tucson Medical Center.

Doctors there were concerned about large purplish bruises on Fabian's forehead and around his penis. Baker told doctors that Fabian had recently fallen several times while walking up the stairs, hitting his head. The bruising around his penis and other areas, she said, probably came from fighting with his older brother, but she wasn't sure.

A CT scan would show a brain hemorrhage, which made Dr. James Splain skeptical.

"The story of trauma is not completely inconsistent with the explanation, although the mechanism seems unlikely to have resulted in a bleed," he wrote in his report. "Combined with his other skin injuries, however, especially the bruise on his penis, I have some suspicion of abuse."

Similarly, Dr. Brian Hagerty, wrote in his report, "The pattern of bruising does concern me for non-accidental injuries."

Fabian stayed under medical care for several days. On the first night a CPS investigator went to the hospital to interview Baker, who talked about how the boy had fallen down the stairs, domestic problems she had with his father and her concerns about her older son being too rough with him.

She also said Romero, who often watched the children alone, smoked marijuana every day because "it helps him get motivated to work," documents show.

Fabian's father, Oscar Silva Jr., and grandmother, Marina Rodriguez, suspected abuse, police reports show. Baker insisted there was none.

In the following days, both the father and the grandmother asked to be interviewed by Kolton. It's unclear if any formal interviews happened, although records show Kolton spoke briefly to Rodriguez over the phone.

Fabian's father also had his oldest son, also named Oscar, write a note to document any abuse.

The boy was 8, and he wrote, "Alex's hites Fabian on the but because Fabian pees. Spanks Fabian because he is bad. Spanks me. spanks me because his kids blame it on me. Me and Fabian get spank all most every day. He hearts my filling. I am righting to my dad. I don't like Alex because I am scared of him."

In an interview with police in February, Kolton said when she interviewed Fabian's older brother, he said none of the claims in the note were true, according to police reports.

"They pretty much disregarded that letter. They didn't take it seriously. It's very frustrating," said Oscar Silva Jr., who recently filed a $5 million claim against the state and CPS.

"There was no forensic interview that I know of," said Jorge Franco Jr., the attorney handling the claim. The police reports don't indicate where the older boy was interviewed or who was present.

"It really is a failure at the individual level. There is always other information out there that's available for (the investigators) to get, and they just don't do it for whatever reason."

Kolton closed the case, saying the reports of abuse were unsubstantiated. Her reasoning, she later told police, was neither Fabian nor his older brother mentioned any abuse, nor did Romero or Baker. She said from talking to the boys she thought the bruising came from a wrestling game.

Franco said that if Kolton had interviewed Fabian's grandparents and father, she would have gotten a different picture. He said young Oscar told his grandparents, "Alex directed and encouraged his own sons to beat up Fabian to 'toughen him' because he was a 'crybaby.' "

Fabian's death

On Jan. 26, Romero drove Baker, with the two boys, from their apartment near West Speedway and North Silverbell Road to the Midtown hair salon where she worked. Then, police reports say, he dropped off Oscar III at SS. Peter and Paul Church, 1436 N. Campbell Ave., for catechism class.

He and Fabian went to the bank and then home, where they played video games.

After about 20 or 25 minutes, though, Romero told police Fabian defecated in his pants. He said he ordered the boy to go upstairs to take a shower, while he went outside to put Christmas lights in a shed.

When Romero came back in Fabian was lying on the floor at the bottom of the stairs. The boy was wearing the same soiled clothes. Even though the boy was unconscious and unresponsive, Romero told police he did not think to call 911 because he "panicked and did not know what to do," the report says.

"He said all that was going through his mind at the time was that Oscar was going to be 'stranded on the side of the road' if he did not pick him up."

Romero told police he put Fabian in the car seat and drove to church, assuming Fabian was asleep because he was "snoring."

It was only after picking up the older brother, Romero said, that Fabian stopped breathing, and he then rushed the boy to University Medical Center, across the street from the church.

Although the hospital staff resuscitated the boy, he died the next day. Doctors estimated Fabian hadn't been breathing for 20 minutes when he arrived at the hospital.

Romero, who is free on bail, would not comment.

CPS records

CPS has also refused to provide Fabian's family with case reports.

For Marina Rodriguez, Fabian's grandmother, the lack of information has made a difficult time that much harder. The case has split apart the family and she feels as if she has been left in the dark.

"I want the proof that they didn't document anything," she said. "It wasn't documented properly. It wasn't followed up properly. What did they do? What did they say when they left the hospital? I want to see the documentation."

The family has been raising funds for a memorial bench, she said, but months after the death, there is no peace.

"Time is not healing anything," she said. "Time is not healing any feelings or emotions, and the loss of Fabian, it's like it was yesterday."

Contact reporter Josh Brodesky at 807-7789 or jbrodesky@azstarnet.com.

Original Article-

Another child's death on CPS' watch raises new questions www.azstarnet.com ®

Restraining orders can be straitjackets on justice

BY MIKE McCORMICK AND GLENN SACKS

Women's advocates in New Jersey fear that a Superior Court judge's ruling in Hudson County will make it harder for women throughout the state to get restraining orders against their male partners.

Certainly abused women need protection and support, but there are many troubling aspects of the Domestic Violence Prevention Act's restraining order provisions that merit judicial or legislative redress

Under the law, it is very easy for a woman to allege domestic violence and get a restraining order (aka "protection order"). New Jersey issues 30,000 restraining orders annually, and men are targeted in four-fifths of them. The standard is "preponderance of the evidence" (often 51 percent to 49 percent), and judges almost always side with the accusing plaintiff.

Under the law, the accuser need not even claim abuse. Alleged ver bal threats of violence are suffi cient, even though it's almost impossible for the accused to provide substantive contradictory evi dence.

The restraining order boots the man out of his own home and generally prohibits him from contact ing his children. Men are cut off from their possessions and property, and some end up in homeless shelters. Yet most have never had a chance to defend themselves in court.

In recognition of the gravity of these orders, the Hudson County judge, Francis Schultz, found the standard of proof unconstitutional and required the stricter "clear and convincing evidence" standard in the case before him. His ruling was not binding on other judges but will likely be appealed, which could lead to a decision with a broader impact.

A large body of evidence shows that restraining orders are frequently misused. For example,the Family Law News, the official publication of the California Bar Association's family law sec tion, recently said:

"Protective orders are increasingly being used in family law cases to help one side jockey for an advantage in child custody ... (they are) almost routinely issued by the court in family law proceedings even when there is relatively meager evidence and usually without notice to the restrained person. ... it is troubling that they appear to be sought more and more frequently for retaliation and litigation purposes."

An article in the November 2007 issue of the Illinois Bar Journal said: "If a parent is willing to abuse the system, it is unlikely the trial court could discover (his or her) improper motives in an order of protection hearing."

These orders have become so commonplace that the Illinois Bar Journal called them "part of the gamesmanship of divorce."

Newark family law attorney Bruce Pitman says, "Anybody who practices family law sees people who abuse the restraining order process. Some create false allegations or take minor or insignificant acts and use them to remove their spouse or partner from the home for advantage in litigation. Such abuses undermine victims of real abuse and violence who seek protection."

Opponents of the ruling point to the relatively rare instances in which men have killed their female partners as evidence for why the law should stand. While these cases are heart-wrenching, they do not constitute a viable argu ment against the ruling. For one, the ruling does not eliminate restraining orders but merely re quires a proper evidence standard for their issuance.

Moreover, it is highly questionable whether restraining orders protect abused women. A violent spouse intent on killing his ex is not going to be deterred from doing so out of fear of violat ing a restraining order. In many domestic violence killings, a restraining order was already in place. In general, a restraining order is enforceable only against a law-abiding, nonviolent man.

Jane Hanson, executive direc tor of Partners for Women and Justice in Montclair, argues that Schultz is wrong in ruling that the Domestic Violence Prevention Act violates parents' "fundamental" right to "be with or maintain their relationship with their children." Yet when a restraining order is issued, fathers can be (and sometimes are) ar rested for calling their children on the phone or going to their Little League games.

Moreover, by removing the father from the home, a custody precedent is set with mom as primary caregiver and dad as occasional visitor -- a precedent that harms fathers' ability to gain joint custody of their children in di vorce proceedings.

Wood calls the law on restraining orders "an efficient system." We disagree. Yes, the system is efficient in separating men from their children and their homes. However, it is hardly efficient in delivering justice.

Mike McCormick is the executive director of the American Coalition for Fathers and Children. Glenn Sacks writes frequently about issues affecting men and fathers.

Link to Original Article --- Restraining orders can be straitjackets on justice - NJ.com

Sunday, July 27, 2008

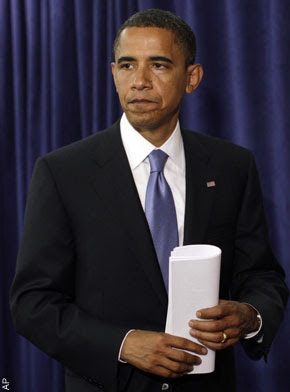

OBAMA'S SECRET RESCUE MISSION

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Some legal stuff I found interesting

I opened it and started to read some of the links within that link..

Man O man.. does this one stay!

Ok so why would you care which links I keep in my legal file and which ones I delete?

Because .. I only share stuff that YOU can use also.. DUH!

For those of us that have overturned the false CPS cases .. we usually don't know which way to turn next ..

check out --

3.13--- Malicious Prosecution-- interesting read

3.30D --- Abuse of Process-- another interesting read!!

3.30E--- Fraud kept my attention for a while also

3.30F--What constitutes -- Intentional Infliction Of Emotional Distress--- is always good to know

Although this link is for New Jersey.. I'm sure you can get a general idea of what you need and then apply it to a search for the same in your State..

CHAPTER ONE - GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS

Instructions To Jurors Before Voir Dire

and MUCH MORE..

Happy searching...

An interesting article on Gag Orders and Domestic Violence survivors

However I'm posting it today for the "UNNAMED" Richmond County IDV judge.. And for the "UNNAMED" penguine co counsel.. and of course for Mr. Wonderful (tongue in cheek) my estranged husband to see...

Do they think I'm a flippin idiot?

Custody case raises energy, awareness

By EMILY PREVITI, epreviti@nwnewsgroup.com

WAUKEGAN - A group of about 10 women waved documents and talked to reporters outside of a courtroom of the Lake County 19th Judicial Circuit Court.

Little of interest had happened in their case; it will continue on Oct. 4.

Yet the women exuded energy as they chatted.

Annette Zender stood watchfully on the periphery of the group.

Zender, of Woodstock, attended court on Sept. 20 to continue to appeal a 2001 custody decision that gave her ex-partner Thomas Boettcher, of Silver Bay, Minn., custody of their child. The couple lived in Lake County at the time.

That day, Associate Judge Jorge Ortiz ordered Zender to pay fees to her child's guardian ad litem, Gary Schlesinger, a Libertyville attorney who has practiced family law for 20 years.

The Illinois Marriage and Dissolution of Marriage Act defines a guardian ad litem as a person, whom the court appoints to make recommendations to the court in the best interests of the child. Those recommendations come only after he or she has interviewed "the child and all parties."

Though Zender and Boettcher did not marry, provisions under acts that govern paternity and adoption extend certain provisions of the Marriage Act regardless of a parent's marital status or biological relationship to the child.

The women who gathered outside of the courtroom belong to the Illinois Coalition for Family Court Reform (ICFCR), which Zender spearheads. The coalition alleges corruption in, and maltreatment by,(Sound familiar to my case?) Cook, DuPage, Kane and Lake Counties' family courts in their dealings with divorce disputes and custody cases. Zender has said she has more than 200 women whose cases illustrate these claims.

On Aug. 30, Judge Joseph Waldeck issued a gag order in Zender's case, which has received extensive coverage by Chicago-area media because of Zender's activities with the coalition. (Again do you see the similarities to my case)

The order prohibits all parties in the case from speaking to the media regarding the case.

(OK... Here is a difference from my case--I'm only banned from naming names--to protect the corruption-- the abuse and blatent disreguard of the law ---being used against numerous domestic violence survivors by Judges including an IDV judge-- or the innocent.. you decide)

Schlesinger, a member of the Illinois State Bar Association, said he had sought the order to protect the child. (Once again notice the similarities in my and this case)

Zender claims the order violates her rights to free speech under the First Amendment. She contends the order intends to prevent putting Lake County's family courts under the microscope.

Larry Schlam, professor of law at Northern Illinois University School of Law, has published several articles on child custody. Schlam contributes to a guide to which Illinois family court judges refer for guidance in some instances. He declined to give the name of the publication, saying that it is not available for public view.

"Trial judges have substantial leeway," he said of the balancing act between a custody case's parties' rights to free speech and the protection of the child.

State law, he expained, provides for the court's prevention of parties from disclosure of a minor's identity. This is not unconstitutional, so long as the identity has not already been disclosed elsewhere, he said.

Zender has published the child's name on the Internet; however, "For Someone Special," a section on the coalition's Web site where Zender had posted messages to her child, whom she has not seen in five years, now reads, "By court order we are no longer able to post personal messages. We hope you understand."

Schlesinger pointed out that, in addition to Internet publishing, the public could determine the child's identity through parents' names.

Once disclosure of the child's name has occured, Schlam said, it cannot be restrained. However, the gag order would hope to diminish further damage to the child, he said.

Schlam said a gag order should be based upon evidence that the child's need for privacy and on evidence that the child would suffer emotional trauma.

"It's common sense," he said. "The kid has a future ... Maybe in 10 years, as a teenager, you might not want people to know what your parents did."

But New Orleans attorney Richard Ducote said the gag order violates Consitutional rights. His child advocacy work spans decades and continents. New Zealand adopted legislation based upon legislation he drafted in 1992.

"[A gag order is] only appropriate in legal proceedings ... to prevent [the] jury from being tainted," he said.

Ducote explained that when judges issue gag orders in custody disputes that lack juries, they do so to "protect the judge and abusers from exposure and accountability."

New York attorney Barry Goldstein, who represents battered mothers, agreed.

"It’s a First Amendment issue," Goldstein said. "Just as the court in New York couldn’t legally do that, nor can Illinois.”

Goldstein said exceptions could be made, but only in “very specific instances [that involve] graphic sexual abuse of child."

Zender has accused her ex-partner of domestic abuse. In July, a former nanny who said she worked for him in April and June contacted Zender with horror stories about his behavior toward her, the child and others.

"If the child is being cared for properly and ... being protected, then no one would need to make comments to the media," Ducote said. "The guardian ad litem [and the] court might not want criticism [or] ... scrutiny."

Ducote said such orders happen often and are rarely appealed or overturned, which Goldstein attributed to parties' fear that antagonizing the judge could compromise their chances to retain or gain custody of their children.

"They have lives of children in their hands," Goldstein said. "Annette has nothing more to lose in terms of antagonizing the judge."

Goldstein met Zender through the Battered Mother's Custody Conference, which will host its fourth summit in January 2007.

Goldstein said he has witnessed decisions based on inaccurate information and the advice of unqualified experts.

"I believe that most cases are not about corruption," he said. "[But] once the court makes a mistake in a domestic violence case, it's not willing to correct it."

Ducote also attributed judicial deficiencies to legal and mental health professionals' misinformation and lack of training, rather than corruption.

Yet he said that gag orders typically stem from a desire to obscure judicial proceedings.

"When courts operate without scrutiny and when fundamental rights are taken away in violation of constitution, it aids - in these family court cases, I have found it to aid abusers getting custody," Ducote said.

"I have just seen too many problems in the court system and abusers getting custody, and accountability of the highest value has to be embraced here."

Link to original Article - Weekly Journals - Custody case raises energy, awareness

Another link ..Great First Amendment web site ..firstamendmentcenter.org: About

Don't miss this article .. Gag Orders

Where in part it states..

A split among circuits

Over time, a split has arisen among federal appeals courts on the standard for evaluating a gag order on trial participants. The Second, Fourth, Fifth and Tenth Circuits have held that a trial court may gag participants if it determines that comments present a "reasonable likelihood" or "substantial likelihood" of prejudicing a fair trial. (In re Dow Jones & Co.; In re Russell; U.S. v. Brown; U.S. v. Tijerina)

Some states have followed the same rule. (Sioux Falls Argus Leader v. Miller; State ex rel. Missoulian v. Montana Twenty-First Jud. Dist. Ct.)

However, the Third, Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Circuits have imposed a stricter standard, rejecting gag orders on trial participants unless there is a "clear and present danger" or "serious and imminent threat" of prejudicing a fair trial. (Bailey v. Systems Innovation, Inc.; U.S. v. Ford; Chicago Council of Lawyers v. Bauer; Levine v. U.S. Dist. Ct.)

Hawaii and New York have followed this standard as well. (Breiner v. Takao; People v. Fioretti)

Yet another interesting story of a custody case... a book exposing corruption... and a gag order.. FOXNews.com - Court Order May Violate First Amendment - Opinion

ABC Does Piece on Child Support Enforcement's Harassment of Soldier in Iraq

ABC in Chicago just did a piece about Army Sergeant Joshua Hinkle, who is battling the state of Illinois over child support while he is stationed in Iraq. I helped one of the ABC producers with the story, and I think they did a good job in explaining Hinkle's side.

Like most so-called "deadbeat dads," Hinkle hasn't been perfect, but he hasn't been bad either. He had a child when he was in high school, and it took him a little while to begin paying child support. He also had problems paying child support during periods of unstable employment.

On the other hand, he has paid a considerable amount of child support and made an honest effort to eliminate his arrearages. It's real hard to see how it benefits his children to have Illinois Division of Child Support harassing him like this. It's also hard to see how it's fair to him.

From Fighting for his country fighting against Illinois (7/23/08):

It is a story of fractured families, empty bank accounts and missing money.

When the I-Team received an email from Army Sergeant Joshua Hinkle a few weeks ago, it first caught our attention because it was sent from Camp Bucca in Iraq.

The soldier wrote that he was suffering a great injustice: the state of illinois, he claimed, had cleaned out his entire bank account for child support.

More here ... GlennSacks.com » Blog Archive » ABC Does Piece on Child Support Enforcement's Harassment of Soldier in Iraq

A collective thank you to Glenn for working on this story...

And for Lizzianthus007 for bringing the original Story to my attention..

Parent's Day

I bet they have something to say about Parents Day today and tomorrow.

15 Thousand Special Parent's Day Messages Sent Out Today, maybe you can cut and paste and send the below to who you know too!

Lary Hollandhttp://www.dcfestival2008.com

Where does your state place in Getting Involved?

Everyone has heard of Mother's Day and Father's Day, but few actually knew there was a collective federal holiday referred to as "Parent's Day" coming up this Sunday until YOU let them know. Be sure to announce it to everyone and we appreciate you taking time out of your day to help make parents important once again. Please publish pertinent information from this message accordingly.

By operation of federal law (US Code, Title 36, Section 135), the fourth Sunday in July is officially known as Parents Day, and every level of local, state and federal government is directed by this law to officially recognize the importance of parents in the lives of children "through proclamations, activities, and educational efforts" - i.e., for once, government HAS to agree with us, and also put it in fancy writing for us, and do something "educational" about it, just for the asking... You can also see the same law here and here and here.

One mayor practically declared war on behalf of parents against government intrusion in this Proclamation that was issued compliments of the United Civil Rights Council of America.

http://unitedcivilrights.org/members/ParentsDay/Proclamations/UT-SandyCity-Mayor.pdf

So as you are enjoying this weekend, know that it is up to you, the press, our churches, our families to remind everyone that government should respect and PROTECT parental rights to be just that...parents.

If you see a mother or a father, remind them that July 27, 2008 is in honor of them and encourage parents to work together on behalf of raising the next significant generation of children that will lead this great nation.

If nothing else, make mention of the National Civil Rights event for parents coming up this August 15 & 16 in honor of all those great parents out there. Many Legislators, Candidates, and Organizations are all in support of parenthood, so spread the word about tomorrow being such an important day. Check out the site as well to see information regarding several Constitutional Amendments being proposed and more.

Where we have a government that thinks it has the apparent authority to confiscate children at will, as we can see from the recent issues in Texas earlier this year, something needs to be done.

Sincerely,Lary Holland

"WRITE TO PARENT"

5119 Highland Rd. #229

Waterford, MI 48327

Additional Inquiries: 800-883-9619

http://www.dcfestival2008.com

'Social workers ripped our family apart for 10 years'

I am publishing the entire article so that if my children follow this blog they will know.. that I will NEVER stop fighting for them.. we will be together again... no matter who has to pay for what they did to me and my 5 babies.. those guilty will pay..God don't like ugly!

Published Date: 26 July 2008

By Tanya Thompson

Social Affairs Correspondent

A GIRL who was taken into care because her mother was accused of child abuse has been reunited with her family after a ten-year ordeal.

The 16-year-old, snatched by social services at the age of six with her younger sister, returned home insisting her mother is innocent and the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

Her mother was accused of having Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBADVERTISEMENTP). Now widely discredited, it is said to be a psychological disorder which leads parents to induce or fabricate illness in their children.

Social services in Dumfries and Galloway refused to return the girls for a decade, insisting they were at risk. Seven years ago, they were put up for adoption and the youngest sister is still with her adoptive parents.

When the older daughter turned 16 earlier this year, she was no longer under the jurisdiction of the courts and chose to return home to her mother.

"I can remember when they took us away, but I didn't understand what was happening," said the teenager. "I was only six. I just remember sobbing.

"I would never want to see this happen to anyone else."

The mother, who cannot be named for legal reasons, always denied harming the children. She says she will fight on to clear her name and is considering legal action.

She claims that her youngest daughter suffered from seizures and other health problems, and that friends and family knew this.

However, after numerous visits to her GP and hospital referrals, social services became suspicious and the woman was accused of having MSBP.

Although it is claimed there were never any physical signs of abuse, the children were taken into care in March 1998.

"I have done nothing wrong and yet my children were taken away from me," the mother said. "I didn't see my daughters for eight years but I never gave up fighting.

"My girls have been deprived of their childhood. That's something they can never get back."

Last night Eric Scott, the family lawyer, said: "I think there was a miscarriage of justice in this case. This requires a public inquiry, looking at how social work departments have been operating.

"A family supporter, the Rev Mike Coley, said he had known the mother for more than a decade and she was incapable of harming her children. He said: "

The children should never have been taken into care."

Dumfries and Galloway Council said it was normal practice to investigate if a child was potentially at risk.

TIMELINE

• March 1998 – The two girls, aged five and six, are taken into care after their mother is suspected of having the condition Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy (MSPB).

• February 2001 – Mother loses legal battle to win back children, who are formally released for adoption.

• 2003 – Sally Clark's conviction for murdering her two young sons is overturned, casting doubt over MSPB.

• January 2004 – Scotsman inquiry reveals 12 parents in Scotland have been accused of having MSBP, resulting in 19 children being placed in care.

• 2008 – The eldest girl turns 16 and decides to return home to her mother.

BACKGROUND

A MOTHER or father is prevented from exercising their parental rights when their child is placed in care.

The children's hearing may or may not decide to allow parents access to a child taken into care.

A decision by the children's panel to take a child from the home can be appealed to the sheriff court by a parent within 21 days. A further appeal can be made to the Court of Session.

Parents have the right to ask for the decision to take their child into care to be reviewed after three months.

Legal aid is usually available to any parent who wishes to challenge such a decision.

Friday, July 25, 2008

The Bill of Rights

The Amendments to the Constitution

Ratified 1791

ARTICLES IN ADDITION TO, AND AMENDMENT OF, THE CONSTITUTION OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PROPOSED BY CONGRESS, AND RATIFIED

BY THE LEGISLATURES OF THE SEVERAL STATES, PURSUANT TO THE 5th

ARTICLE OF THE ORIGINAL CONSTITUTION.

(The first 10 Amendments were ratified 15 December 1791, and

form what is known as the 'Bill of Rights'.)

AMENDMENT I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,

freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people

peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a re-

dress of grievances.

AMENDMENT II

A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a

free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall

not be infringed.

AMENDMENT III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house,

without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a

manner to be prescribed by law.

AMENDMENT IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses,

papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures,

shall not be violated; and no Warrants shall issue, but upon

probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particu-

larly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or

things to be seized.

AMENDMENT V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise

infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand

Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in

the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public

danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to

be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled

in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be

deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of

law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without

just compensation.

AMENDMENT VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right

to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State

and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which

district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to

be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be

confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory

process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the

Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

AMENDMENT VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall

exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be

preserved, and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise

reexamined in any Court of the United States, than according to

the rules of the common law.

AMENDMENT VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed,

AMENDMENT IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall

not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the

people.

AMENDMENT X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution,

States respectively, or to the people.

The Declaration of Independence

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves

invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his

Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns,

and destroyed the Lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely

paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the

Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high

Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an

undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury.

A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to

be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attention to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably

interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our

Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions,

do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent

States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally

dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which

Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the Protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our

Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

JOHN HANCOCK, President

Attested, CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary

New Hampshire

JOSIAH BARTLETT

WILLIAM WHIPPLE

MATTHEW THORNTON

Massachusetts-Bay

SAMUEL ADAMS

JOHN ADAMS

ROBERT TREAT PAINE

ELBRIDGE GERRY

Rhode Island

STEPHEN HOPKINS

WILLIAM ELLERY

Connecticut

ROGER SHERMAN

SAMUEL HUNTINGTON

WILLIAM WILLIAMS

OLIVER WOLCOTT

Georgia

BUTTON GWINNETT

LYMAN HALL

GEO. WALTON

Maryland

SAMUEL CHASE

WILLIAM PACA

THOMAS STONE

CHARLES CARROLL

OF CARROLLTON

Virginia

GEORGE WYTHE

RICHARD HENRY LEE

THOMAS JEFFERSON

BENJAMIN HARRISON

THOMAS NELSON, JR.

FRANCIS LIGHTFOOT LEE

CARTER BRAXTON.

New York

WILLIAM FLOYD

PHILIP LIVINGSTON

FRANCIS LEWIS

LEWIS MORRIS

Pennsylvania

ROBERT MORRIS

BENJAMIN RUSH

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

JOHN MORTON

GEORGE CLYMER

JAMES SMITH

GEORGE TAYLOR

JAMES WILSON

GEORGE ROSS

Delaware

CAESAR RODNEY

GEORGE READ

THOMAS M'KEAN

North Carolina

WILLIAM HOOPER

JOSEPH HEWES

JOHN PENN

South Carolina

EDWARD RUTLEDGE

THOMAS HEYWARD, JR.

THOMAS LYNCH, JR.

ARTHUR MIDDLETON

New Jersey

RICHARD STOCKTON

JOHN WITHERSPOON

FRANCIS HOPKINS

JOHN HART

ABRAHAM CLARK

What the hell happened?

(Thanks Ali)

Food for thought.

How many zeros in a billion?

This is too true to be funny

The next time you hear a politician use the word 'billion' in a casual manner, think about whether you want the 'politicians' spending YOUR tax money.

A billion is a difficult number to comprehend, but one advertising agency did a good job of putting that figure into some perspective in one of it's releases.

1. A billion seconds ago it was 1959.

2. A billion minutes ago Jesus was alive.

3. A billion hours ago our ancestors were living in the Stone Age.

4. A billion days ago no-one walked on the earth on two feet.

5. A billion dollars ago was only 8 hours and 20 minutes, at the rate our government is spending it.

While this thought is still fresh in our brain... let's take a look at New Orleans It's amazing what you can learn with some simple division.

Louisiana Senator, Mary Landrieu (D) is presently asking Congress for 250 BILLION DOLLARS to rebuild New Orleans Interesting number... what does it mean?

1. Well... if you are one of the 484,674 residents of New Orleans (every man, woman, and child) you each get $516,528.

2. Or... if you have one of the 188,251 homes in New Orleans , your home gets $1,329,787.

3. Or... if you are a family of four... your family gets $2,066,012.

Washington, D. C HELLO! Are all your calculators broken??

Accounts Receivable Tax

Building Permit Tax

CDL License Tax

Cigarette Tax

Corporate Income Tax

Dog License Tax

Federal Income Tax

Federal Unemployment Tax (FUTA)

Fishing License Tax

Food License Tax

Fuel Permit Tax

Gasoline Tax

Hunting License Tax

Inheritance Tax

Inventory Tax

IRS Interest Charges (tax on top of tax)

IRS Penalties (tax on top of tax)

Liquor Tax

Luxury Tax

Marriage License Tax

Medicare Tax

Property Tax

Real Estate Tax

Service charge taxes

Social Security Tax

Road Usage Tax (Truckers)

Sales Taxes

Recreational Vehicle Tax

School Tax

State Income Tax

State Unemployment Tax (SUTA)

Telephone Federal Excise Tax

Telephone Federal Universal Service Fee Tax

Telephone Federal, State and Local Surcharge Tax

Telephone Minimum Usage Surcharge Tax

Telephone Recurring and Non-recurring Charges Tax

Telephone State and Local Tax> Telephone Usage Charge Tax

Utility Tax

Vehicle License Registration Tax

Vehicle Sales Tax

Watercraft Registration Tax

Well Permit Tax

Workers Compensation Tax

STILL THINK THIS IS FUNNY?

Not one of these taxes existed 100 years ago... and our nation was the most prosperous in the world.

We had absolutely no national debt... We had the largest middle class in the world... and Mom stayed home to raise the kids.

What happened?

Can you spell 'politicians!'

And I still have to press "1" for English.

I hope this goes around the USA at least 100 times

What the HELL happened?????

More from Expose Corrupt Courts ...

Now when I opened my Blog today .. glanced over at my favorite website on corruption in the courts and found this...

Friday, July 25, 2008

Federal Complaint: NYS Commission on Judicial Conduct is Corrupt

Federal Complaint: New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct is CorruptA filing in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York says New York’s Commission on Judicial Conduct (SCJC) is a “sham” operation designed to protect certain political insiders, and to target, chill and destroy other “non-player” justices throughout the empire state.

I have to ask myself.. why wasn't I the least bit shocked?

Check out the link above for more....

Thursday, July 24, 2008

"Misprision of a Felony"

Don't miss this article today in Expose Corrupt Courts ..

"Misprision of a felony" Charges Needed in NY to Clean-Up Court Corruption

MISPRISION OF FELONY - Whoever, having knowledge of the actual commission of a felony cognizable by a court of the U.S., conceals and does not as soon as possible make known the same to some judge or other person in civil or military authority under the U.S. 18 USC. Misprision of felony, is the like concealment of felony, without giving any degree of maintenance to the felon for if any aid be given him, the party becomes an accessory after the fact.

Expose Corrupt Courts: "Misprision of a felony" Charges Needed in NY to Clean-Up Court Corruption

Immunity as ruled by the US Supreme Court

35 PAGES IN GA==IMMUNITY CASES-MY DOCS-BLACKSTICK-ICE

Supreme Court's views as to application or applicability of doctrine of qualified immunity in action under 42 USCS § 1983, or in Bivens action, seeking damages for alleged civil rights violations. 116 L Ed 2d 965.

QUALIFIED IMMUNITY-MEMO

TITLE 69. CIVIL RIGHTS

III. LIABILITY AND REMEDIES FOR INFRINGEMENT

(B) UNDER FEDERAL LAW

2. Under Federal Civil Rights Legislation, In General.

69 L Ed Digest §32

Public defenders are not immune from liability under 42 USCS § 1983 for intentional misconduct, under color of state law, by virtue of alleged conspiratorial action with state officials that deprives their clients of federal rights. Tower v Glover, 467 US 914, 104 S Ct 2820, 81 L Ed 2d 758

§ 32 sovereign, governmental, or official immunity.

Return to the TOC

Search All Supreme Court Cases Classified under this Section

View Research and Cross References

CASE-NOTES:

The Civil Rights Statutes (8 USCS §§ 43, 47 (3)), which provide a civil remedy against those who, under color of state law, deprive, or conspire to deprive, a person of rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Federal Constitution do not abolish the ancient rule under which legislators are immune from liability for acts done within the sphere of legislative activity. Hence no cause of action is stated by a complaint in an action to recover damages under these statutes in which it is alleged that the defendants, members of a state legislative committee constituted to inquire into un-American activities, summoned plaintiff to appear before them at a hearing, initiated contempt proceedings, and did other acts for the purpose of intimidating and silencing him and deterring him from effectively exercising his constitutional rights, such as the right of free speech and to petition the legislature for redress of grievances. (Douglas, J., dissented from this holding.) Tenney v Brandhove, 341 US 367, 71 S Ct 783, 95 L Ed 1019

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***

Note Distinguished in Richardson v McKnight, 521 US 399, 138 L Ed 2d 540, 117 S Ct 2100, holding that two prison guards, who were employees of private firm that managed state correctional center, were not entitled to qualified immunity from 42 USCS § 1983 suit by prisoner at center.

The common-law doctrine of immunity of judges from liability for damages for acts committed within their judicial jurisdiction is not abolished by § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (42 USCS § 1983) which makes liable "every person" who under color of law deprives another person of his civil rights. (Douglas, J., dissented from this holding.) Pierson v Ray, 386 US 547, 87 S Ct 1213, 18 L Ed 2d 288

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***

Note Distinguished in Richardson v McKnight, 521 US 399, 138 L Ed 2d 540, 117 S Ct 2100, holding that two prison guards, who were employees of private firm that managed state correctional center, were not entitled to qualified immunity from 42 USCS § 1983 suit by prisoner at center.

Government officials, as a class, cannot be totally exempt, by virtue of some absolute immunity, from liability under the terms of 42 USCS § 1983, providing for a civil action for violation of federal rights, since the statute includes within its scope the misuse of power possessed by virtue of state law and made possible only because the wrongdoer is clothed with the authority of state law. Scheuer v Rhodes, 416 US 232, 94 S Ct 1683, 40 L Ed 2d 90

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***In determining whether public school officials are immune from liability for damages claimed under 42 USCS § 1983, providing for a civil action for violation of federal rights, because they acted in good faith in expelling high school students from school for violation of a school regulation, the appropriate test of good faith necessarily contains both objective and subjective elements; the official must himself be acting sincerely and with a belief that he is doing right, but an act violating a student's constitutional rights can be no more justified by ignorance or disregard of settled, indisputable law on the part of one entrusted with supervision of students' daily lives than by the presence of actual malice; to be entitled to a special exemption from the categorical remedial language of § 1983 in a case in which this action violated a student's constitutional rights, a school board member, who has voluntarily undertaken the task of supervising the operation of the school and the activities of the students, must be held to a standard of conduct based not only on permissible intentions, but also on knowledge of the basic unquestioned constitutional rights of his charges. (Powell, J., Burger, Ch. J., and Blackmun and Rehnquist, JJ., dissented from this holding.) Wood v Strickland, 420 US 308, 95 S Ct 992, 43 L Ed 2d 214

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***A state prosecuting attorney who acted within the scope of his duties in initiating and pursuing a criminal prosecution and in presenting the state's case is absolutely immune from a civil suit for damages for alleged deprivations of the defendant's constitutional rights under 42 USCS § 1983, which provides that every person who acts under color of state law to deprive another of a constitutional right shall be liable to the injured party in an action at law. Imbler v Pachtman, 424 US 409, 96 S Ct 984, 47 L Ed 2d 128

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** Note Distinguished in Burns v Reed, 500 US 478, 114 L Ed 2d 547, 111 S Ct 1934, holding that, for purposes of damages liability under 42 USCS § 1983, local prosecutor was entitled to absolute immunity for participation in probable cause hearing to obtain search warrant, but to only qualified immunity for giving legal advice to police in investigative phase of criminal case; Antoine v Byers & Anderson, Inc., 508 US 429, 124 L Ed 2d 391, 113 S Ct 2167, holding that court reporter for Federal District Court was not absolutely immune from damages liability for failing to produce transcript of federal criminal trial.

A state prosecutor's absolute immunity from liability for damages under 42 USCS § 1983 for acts done in the scope of his duties in initiating and prosecuting a case, which acts allegedly deprived the accused of constitutional rights is applicable even where the prosecutor (1) knowingly used perjured testimony at the trial, (2) deliberately withheld exculpatory information, or (3) failed to make a full disclosure of all facts casting doubt upon the state's testimony. (White, Brennan, and Marshall, JJ., dissented in part from this holding.) Imbler v Pachtman, 424 US 409, 96 S Ct 984, 47 L Ed 2d 128

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***Note Distinguished in Burns v Reed, 500 US 478, 114 L Ed 2d 547, 111 S Ct 1934, holding that, for purposes of damages liability under 42 USCS § 1983, local prosecutor was entitled to absolute immunity for participation in probable cause hearing to obtain search warrant, but to only qualified immunity for giving legal advice to police in investigative phase of criminal case; Antoine v Byers & Anderson, Inc., 508 US 429, 124 L Ed 2d 391, 113 S Ct 2167, holding that court reporter for Federal District Court was not absolutely immune from damages liability for failing to produce transcript of federal criminal trial.

A prosecutor, acting within the scope of his duties in initiating and prosecuting a case, has the same absolute immunity from liability for damages under 42 USCS § 1983 for alleged violation of another's constitutional rights that a prosecutor enjoys at common law, notwithstanding that such immunity leaves the genuinely wronged defendant without civil redress against a prosecutor whose malicious or dishonest action deprives him of liberty; there is not exception to such prosecutorial immunity even where the person asserting violation of his civil rights has successfully petitioned for habeas corpus relief. Imbler v Pachtman, 424 US 409, 96 S Ct 984, 47 L Ed 2d 128

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***Note Distinguished in Burns v Reed, 500 US 478, 114 L Ed 2d 547, 111 S Ct 1934, holding that, for purposes of damages liability under 42 USCS § 1983, local prosecutor was entitled to absolute immunity for participation in probable cause hearing to obtain search warrant, but to only qualified immunity for giving legal advice to police in investigative phase of criminal case; Antoine v Byers & Anderson, Inc., 508 US 429, 124 L Ed 2d 391, 113 S Ct 2167, holding that court reporter for Federal District Court was not absolutely immune from damages liability for failing to produce transcript of federal criminal trial.

In an action under 42 USCS § 1983 against state prison officials, such officials are immune from liability as to a state prisoner's claim arising out of the officials' alleged unconstitutional interference with the state prisoner's outgoing mail, where (1) at the time of the alleged misconduct of the officials there was no clearly established First and Fourteenth Amendment right with respect to the correspondence of convicted prisoners, and (2) the prisoner's claim for relief asserted that prison officials negligently and inadvertently interfered with mail and that prison supervisory officials negligently failed to provide proper training to their subordinates. (Burger, Ch. J., and Stevens, J., dissented.) Procunier v Navarette, 434 US 555, 98 S Ct 855, 55 L Ed 2d 24

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** Note Distinguished in Richardson v McKnight, 521 US 399, 138 L Ed 2d 540, 117 S Ct 2100, holding that two prison guards, who were employees of private firm that managed state correctional center, were not entitled to qualified immunity from 42 USCS § 1983 suit by prisoner at center.

In an action for damages under 42 USCS § 1983 a qualified immunity from damages is available to a state governor, a president of a state university, and officers and members of a state national guard; the same is true of local school board members, of the superintendent of a state hospital, and of local policemen. Procunier v Navarette, 434 US 555, 98 S Ct 855, 55 L Ed 2d 24

All Federal & State Citing Cases

In a suit brought against state prison officials for damages under 42 USCS § 1983 arising from the actions of the officials which allegedly violated federal constitutional rights of a state prisoner, the state prison officials are entitled to qualified, rather than absolute, immunity from liability; the immunity defense is unavailing to the prison officials (1) if the constitutional rights allegedly infringed by them were clearly established at the time of their challenged conduct, they knew or should have known of the rights, and they knew or should have known that their conduct violated the constitutional norms, or (2) if they acted with malicious intention to deprive the prisoner of constitutional rights or to cause him other injury. Procunier v Navarette, 434 US 555, 98 S Ct 855, 55 L Ed 2d 24

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** "Intentional injury," contemplating that the actor intends the consequences of his conduct, is involved in the rule governing qualified immunity whereby a state official sued for damages under 42 USCS § 1983 is not immune from suit when the official acted with "malicious intention" to deprive the plaintiff of a constitutional right or to cause him "other injury." Procunier v Navarette, 434 US 555, 98 S Ct 855, 55 L Ed 2d 24

All Federal & State Citing Cases

State-law immunities do not override a cause of action under 42 USCS § 1983, which imposes civil liability on any person who deprives another of his federally protected rights. Monell v Department of Social Services, 436 US 658, 98 S Ct 2018, 56 L Ed 2d 611

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** In the absence of congressional direction to the contrary, a higher degree of immunity from liability is not to be accorded to federal officials when sued for a constitutional violation than is accorded to state officials when sued for the identical violation under 42 USCS § 1983. Butz v Economou, 438 US 478, 98 S Ct 2894, 57 L Ed 2d 895

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** It is untenable to draw a distinction for purposes of immunity law between suits brought against state officials under 42 USCS § 1983 and suits brought directly under the Federal Constitution against federal officials. Butz v Economou, 438 US 478, 98 S Ct 2894, 57 L Ed 2d 895

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***42 USCS § 1983 which provides a right of action against any "person" who deprives, under color of state law, another of federal civil rights, does not override the traditional sovereign immunity of the states as guaranteed by the Eleventh Amendment. Quern v Jordan, 440 US 332, 99 S Ct 1139, 59 L Ed 2d 358

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** A state statute which grants public officials immunity from liability for any injury resulting from a parole release determination does not control a claim asserted in a state court under 42 USCS § 1983 against state officials by the survivors of an individual who was murdered by a parolee, such claim alleging that the officials, by their actions in releasing the parolee, had subjected the decedent to a deprivation of life without due process of law; conduct by persons acting under color of state law which is wrongful under 42 USCS § 1983 or 42 USCS § 1985(3) cannot be immunized by state law. Martinez v California, 444 US 277, 100 S Ct 553, 62 L Ed 2d 481

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***In an action brought against a municipality under 42 USCS § 1983 for depriving a person of federally protected rights, the municipality is not entitled to qualified immunity from liability by asserting the good faith of its officers or agents as a defense to liability under § 1983. (Powell, J., Burger, Ch. J., and Stewart and Rehnquist, JJ., dissented from this holding.) Owen v Independence, 445 US 622, 100 S Ct 1398, 63 L Ed 2d 673

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** The applicable test for determining establishment of the qualified immunity defense to damages liability under 42 USCS § 1983 that is available to executive officers for acts performed in the course of official conduct focuses not only on whether the official had an objectively reasonable belief that his conduct was lawful, but also on whether the official himself was acting sincerely and with a belief that he was doing right. Gomez v Toledo, 446 US 635, 100 S Ct 1920, 64 L Ed 2d 572

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** A state's highest court and its members are acting in their legislative capacity and are immune from suit under 42 USCS § 1983 with respect to the issuance of a state code of professional responsibility governing the conduct of attorneys, where the court, claiming inherent power to regulate the bar, exercises the state's entire legislative capacity with respect to regulating the bar, and the court's members are the state's legislators for the purpose of issuing the code. Supreme Court of Virginia v Consumers Union of United States, Inc., 446 US 719, 100 S Ct 1967, 64 L Ed 2d 641

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** State legislators' common-law immunity from liability for their legislative acts extends to civil rights actions seeking declaratory or injunctive relief under 42 USCS § 1983 as well as to actions seeking damages. Supreme Court of Virginia v Consumers Union of United States, Inc., 446 US 719, 100 S Ct 1967, 64 L Ed 2d 641

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***Although the separation of powers doctrine justifies a broader privilege for Congressmen than for state legislators in criminal actions, the legislative immunity to which state legislators are entitled under 42 USCS § 1983 is equivalent to that accorded Congressmen under the Constitution. Supreme Court of Virginia v Consumers Union of United States, Inc., 446 US 719, 100 S Ct 1967, 64 L Ed 2d 641

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** Prosecutors enjoy absolute immunity from damages liability under 42 USCS § 1983, but they are natural targets for injunctive suits under 42 USCS § 1983 since they are the state officers who are threatening to enforce and who are enforcing the law. Supreme Court of Virginia v Consumers Union of United States, Inc., 446 US 719, 100 S Ct 1967, 64 L Ed 2d 641

All Federal & State Citing Cases

***A state official claiming immunity from liability under 42 USCS § 1983 has the burden of demonstrating his entitlement thereto. Dennis v Sparks, 449 US 24, 101 S Ct 183, 66 L Ed 2d 185

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** The decisions of the United States Supreme Court recognizing absolute immunity for judges and prosecutors from civil liability under § 1 of the 1871 Civil Rights Act (42 USCS § 1983) implicitly reject the position that the legislative history of the 1866 Civil Rights Act defines the scope of immunities for purposes of the 1871 Act. Briscoe v LaHue, 460 US 325, 103 S Ct 1108, 75 L Ed 2d 96

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** Immunity analysis rests on functional categories, not on the status of a defendant; a police officer on the witness stand performs the same functions as any other witness and he is subject to compulsory process, takes an oath, responds to questions on direct examination and cross-examination, and may be prosecuted subsequently for perjury; to the extent that traditional reasons for witness immunity are less applicable to government witnesses, other considerations of public policy support absolute immunity for such witnesses more emphatically than for ordinary witnesses; subjecting government officials, such as police officers, to damages liability under 42 USCS § 1983 for their testimony might undermine not only their contribution to the judicial process but also the effective performance of their other public duties since § 1983 lawsuits against police officer witnesses, like lawsuits against prosecutors, could be expected with some frequency and could be very time-consuming, imposing significant burdens on the judicial system and on law-enforcement resources. (Brennan, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ., dissented from this holding.) Briscoe v LaHue, 460 US 325, 103 S Ct 1108, 75 L Ed 2d 96

All Federal & State Citing Cases

*** There is no exception to the rule that police officers are immune from civil liability for damages under 42 USCS § 1983 for alleged violation of another's constitutional rights even where the person asserting violation of his civil rights has successfully vindicated himself in another forum, either on appeal or by collateral attack, since, in determining whether to grant post-conviction relief, the tribunal should focus solely on whether there was a fair trial under law and should not have its focus blurred by even the subconscious knowledge that a post-trial decision in favor of the accused might result in the police officer's being called upon to respond in damages; it is not for the United States Supreme Court to craft a new rule designed to enable trial judges to dismiss meritless claims before trial but to allow recovery in cases of demonstrated injustice, when an innocent plaintiff has already obtained post-conviction relief. Briscoe v LaHue, 460 US 325, 103 S Ct 1108, 75 L Ed 2d 96

All Federal & State Citing Cases